Tobacco Baskets

Baity Basket Manufacturing Company

For the first sixty or so years of the twentieth century, the auction warehouses used these baskets to move tobaccos. The basket, thirty-eight inches square and five inches deep, was designed for two men to carry. Each basket was piled with about two hundred pounds of leaf.

My mother’s family, the Baitys, were basket makers. The family had moved from Courtney in Yadkin County to Winston-Salem, and Grandfather Isaac Israel Baity was a night watchman at a warehouse. Times must have been tough – my grandmother, Sallie Baity, took in boarders to supplement the family income. My uncle, Clyde Newsome (Newn) Baity, born in 1902, went to work at RJR operating an elevator when he was thirteen.

They returned to Courtney in 1919 and opened a backyard shop where they made oak water buckets and oak whiskey barrels. They expanded into tobacco baskets and started the Baity Basket Manufacturing Company, eventually buying a 2.75 acre plant site. The abandoned shop office still stands today at Courtney crossroad. In the 1950s Baity Basket was the largest employer in the county, a mostly agricultural region. From 1920 to 1968, this little business made more than four million baskets, and their trucks hauled them to tobacco warehouses from northern Florida to southern Maryland and as far west as Paducah, Kentucky.

The baskets were made from woven white oak “splits”. White oak would split cleanly and evenly into strong thin strips that could curve without breaking. Each split was hand “rived“ from a block of timber, using a special blade and mallet. Local people, mostly in their spare time, made these splits and sold them to basket makers.

My paternal grandfather, Jasper Hoots, continued to rive splits when he was too old to do heavy farm work in the 1960s. Baity Basket paid $1.50 for a bundle of fifty splits. They now are $75 per bundle.

The basket finally yielded to technology. The forklift and a simple burlap cloth that could wrap the leaves made the basket obsolete. Today, baskets are used only decoratively, sometimes converted into coffee tables.

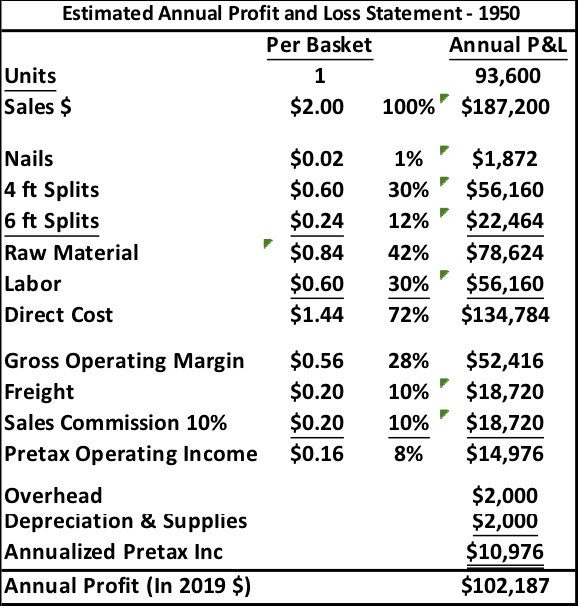

Few financial records of Baity Basket have survived, but the business must have been profitable. With a daily output of four hundred fifty baskets, the shop operated only nine months a year. In the 1930s, this business made a profit of about $11,000 ($207,000-2020). C. N. Baity, 50% owner, said that he had accumulated $40,000 ($737,000 in $2020) to build the High Point Motor Speedway in 1940. The Baitys were early stockcar racing enthusiasts.

My Uncle Ken Hoots grew up in the Deep Creek – Courtney community. He said that while the Baitys certainly were not wealthy, “They had ‘something’ when everybody else had ‘nothing’,” referring to the Great Depression years. Across North Carolina many entrepreneurs like Ike and Newn Baity played at least a small part in the economic development fed by tobacco, bringing employment to depressed parts of the state.

Basket Economics

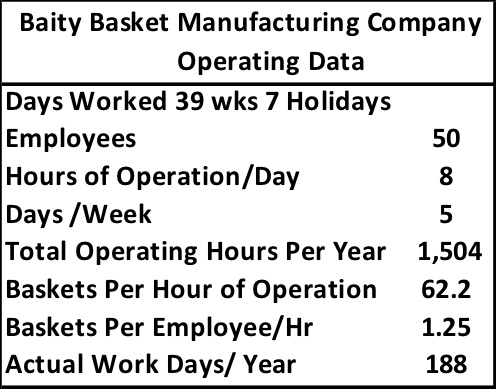

Baity Basket was a typical small business that depended on tobacco. Started in their backyard, a father and son, it operated seasonally, closing during the winter months. The basket “shop” was a roofed shed with no sides.

They sold baskets from 1920-68, forty-four years of production – for four years operations were suspended during World War II. Five Yadkin County basket shops made most tobacco baskets. This manufacturing concentration was probably the result of an available workforce, a good supply of white oak, and the central location in the heart of the tobacco belt.

Baity’s average annual production approached 100,000 baskets but was certainly higher in its early decades. This little shop made over four million baskets, and the industry made millions more. An estimated profit statement for a typical year, 1950 indicates a profit of $11,000. But the great era of basket production was the late 1920s and early 1930s, when profits perhaps exceeded what is shown here (in inflation-adjusted terms). If the profit margin was constant, not an unreasonable assumption, then the profit adjusted for inflation was about constant. ($117,000-2020).

Whatever the actual profit, C. N. Baity, who owned 50% of the business, made a comfortable living. When Isaac Baity died, his other three sons and his widow equally divided his 50%. Profits were enough to supplement the sons’ income and to support the widow. Such small businesses depended on the gold leaf just as much as the people who grew the tobacco. The sale of all the supplies – seed, fertilizer, animal feed, tools, and scores of other items depended on the success of the tobacco crop each year. Local people in their spare time, hewed the white oak splits and sold them to Baity Basket, another example of tobacco-related income. It is impossible to overstate the second and third levels of business in North Carolina that very much depended on tobacco for a “trickle-down” effect.

Basket Shop Memories

Several family members who worked at the shop shared their memories. These all fit the pattern of the tobacco culture, even though their work was in a shop and not in the fields. The hard work taught life lessons they never forgot.

“I can still recall my first day at work at the basket shop. My father gave me my Social Security card and I started painting baskets. I was 11! Child labor laws didn’t exist back then, fortunately, ‘cause I learned a lot from working there. Most importantly, I never wanted to do that kind of work for the rest of my life!”

Colonel Mickey Baity USAF (Ret.)

“I am the grandson of C.N. and Carrie Baity of Courtney, NC. When I was young, back in the late 1950s and early 1960s, I would spend a week or two each summer with my grandparents, and other extended family, in Courtney. Those summer trips are some of the best memories of my childhood.

While there, I was able to walk a short distance down the road to my grandfather’s (we always called him Pa) business, the Baity Basket Manufacturing Company. I believe this was the heyday of the tobacco basket making business.

Even though I was only 8 or 10 or 12 years old, I was welcome at the shop and allowed to help make a few baskets.

I recall the process went something like this…thin, narrow wooden slats were woven into a pattern that would later be shaped. This wooden weave was dipped into a hot solution of some kind and then a press shaped the slats into the traditional shape of tobacco baskets. The best I remember, my job was to take small nails and hammer the slats together.

The most unique aspect of the process, at least to me, was the hammer we used. The metal end had the head of a hammer on one side, and a hatchet blade on the other. The hatchet side also had a slot that was perfect for pulling any ill-placed nails.

This was all great fun for me. While I was too young and small to produce much, I am proud to say I at least had a hand in making some of the finest tobacco baskets made!

And the day was not complete without a trip to Gurnie’s store for a Truade orange and oatmeal cookie.

Great, great memories.”

Reverend Myke Dickens, Arizona State University

9/25/17 Notes from Charles Baity, son of Baity Basket co-founder, in conversation with the author September 15, 2017