Myrtle Beach Farms

One of the most interesting deals was Myrtle Beach Farms, owner of much of Myrtle Beach, SC. Most people today are familiar with the Grand Strand, but probably know very little about its history or how it developed. And almost nobody ever knew of RJR’s interest in Myrtle Beach.

In May 1971, RJR sold some if its Penick & Ford operations and realized a capital tax loss of $29 million. The company had no way to generate capital gains to offset this loss, and the deduction was worth several million dollars in tax benefits to the company. Reynolds was searching for a way to create a capital gain when an opportunity presented itself. Investment bankers at the Bank of North Carolina in Charlotte (now Bank of America) approached Reynolds about buying Myrtle Beach Farms.

Myrtle Beach was a popular resort that showed promise as a golf center for people outside the Southeast but was still a regional vacation destination mainly in the summer months. The Grand Strand stretched along the South Carolina coast for seventy miles, south of North Carolina, and Myrtle Beach was the most popular destination in this coastal region.

Myrtle Beach Farms owned much of the real estate in the Myrtle Beach section. Seventy years earlier, it had owned virtually all of what came to be known as Myrtle Beach. It had an interesting history, tracing back to before the Civil War. (See the following Chronology).

The Burroughs family controlled the business. They were in many ways, “land poor.” Their holdings were enormously valuable but produced relatively little income. The family had sold its property in the late 1920s to a developer who built an oceanfront hotel, the Ocean Forest, a landmark that stood for decades. Unfortunately, the Great Depression disrupted the developers’ plans and they declared bankruptcy and the Burroughs family repossessed the property. Their cost basis was the price for which they had sold the land before the Depression. So, forty or so years later they held greatly appreciated assets.

Their bankers saw an opportunity to match RJR ‘s need for capital gains with the Burroughs family’s desire for liquidity. The bankers proposed that RJR do a tax-free exchange of RJR’s common shares for the shares of Myrtle Beach Farms. Eventually, RJR could sell the property for long-term capital gains, offsetting the losses that Reynolds had on his books.

In the fall of 1971, I was working in the merger and acquisition area, reporting to Bill Lybrook, the corporate secretary and nephew of R. J. and Will Reynolds. Bill was very interested in the project. He sent me to study the possibility of an acquisition.

I moved to the St. John’s Inn at Myrtle Beach and was there most of the time from Labor Day until Thanksgiving. I coordinated with two real estate appraisers from Myrtle Beach and Charleston. They made independent detailed appraisals of the properties.

This property inventory included 500 or so develop lots in Myrtle Beach, the Myrtle Beach Pavilion, a thousand acres on the west side of the inland waterway, and a huge tract of land south of Myrtle Beach not far from the Air Force base. The crown jewel was almost a mile of beachfront directly south of the Dunes Club, a local high-end residential golf community and country club. Bill Lybrook described it as probably the most valuable stretch of undeveloped beachfront on the eastern seaboard, and he may well have been right. I still have the original copies of the two appraisal reports as well as my own valuation. It is eye-opening to study those old maps of undeveloped land and then visit the area now. The change is beyond anything I would have imagined in 1971.

At that time, Myrtle Beach was a popular summer resort but with little business in other seasons. One evening I returned to the St. John’s and the young lady at the reception desk said, “If you hear any noise tonight, would you please check it out.” I asked what she meant, and she told me that I was the only person staying in the Inn that evening, and she was going home. It was a bit strange staying in a large resort with nobody else about. People who visit Myrtle Beach today in the winter would find it hard to believe how deserted the place could be after Labor Day forty-eight years ago.

So often during my years at RJR, work afforded me the opportunity to meet some very fine people. On this venture, I worked with the investment banker from NCNB, Buddy Kemp. Buddy was impressive – a graduate of Davidson and Harvard Business School. We got to know each other fairly well, and from his comments, it was obvious that he was going to rise in Hugh McColl’s bank. He was later dispatched to run their Texas operations after NCNB made large banking acquisitions there. Unfortunately, he developed a brain tumor and died at an early age. I often wondered what the future of the Bank would have been, had he lived. His peers have told me that he definitely was the “heir apparent” to Hugh McColl. They feel that under his leadership the bank would have gone in a different direction. Of course, whether that direction might have kept Bank America from some of its later troubles, we will never know.

Another person I thoroughly enjoyed was Mr. Ed Burroughs, the family patriarch. He was the only family member I dealt with – a real gentleman and a pleasure to know. As I recall, he was born in 1900 and was seventy-one years old when I worked with him. He told me that Myrtle Beach Farms had been a real operating farm and that he had herded hogs on the beach as a child.

Buddy Kemp, told me that Mr. Burroughs had been an owner of the Pine Lakes Country Club, located in the heart of Myrtle Beach and that the owners had sold it for $50,000. I asked Burroughs about that, and he said it was true. He explained, “I was in a small group who bought it in 1940 for $50,000. You must remember, at that time a man who had $50,000 was a fool to spend it on anything. He could live very well on the interest from that much money. But my little group owned it for a few months, and we got a weekly profit statement that showed us that we were losing four or five dollars every week. So, we found someone more ‘foolish’ than we were and sold it to them for $50,000 and got our money back.” In 1971, the clubhouse alone could not be replaced for $1 million. The club and golf course are still there, and it is hard to imagine what that property is worth now.

In the end, RJR declined to buy the property. There were concerns that we would not have the expertise to manage a real estate operation of this magnitude. I understood from Buddy Kemp that our rejection was something of an embarrassment for Mr. Burroughs. He had represented this to his family as an opportunity for them to gain liquidity, and he felt, with some justification, that we had let him down.

However, RJR not buying Myrtle Beach Farms was probably the best thing that could’ve ever happened to the family. While our stock would have provided liquidity, the unforeseen explosion of the Grand Strand as a destination resort has made their real estate more valuable than the RJR are stock would have been.

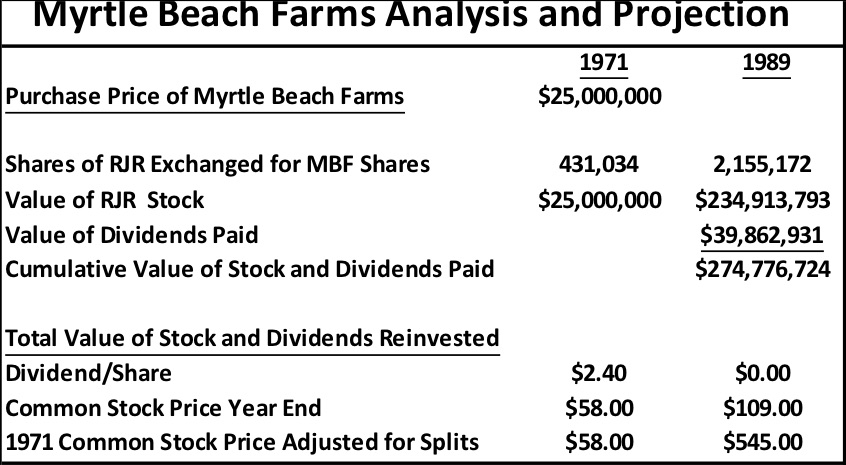

The proposal was to swap Myrtle Beach Farms stock for $25 million in RJR common stock, 431,000 shares. Had the Burroughs family taken the stock, in 1989, their stock and dividends would have totaled $275 million dollars. As a further “what if,” with the dividends reinvested in RJR stock, the value would have been $425 million. Over the following thirty years until now, a reasonable return might have been 6 percent, giving the family $2.5 billion.

I often speculated on what happened to Myrtle Beach Farms, and by coincidence, a lady I met in Charlotte happened to be a childhood friend of one of the family, Egerton Burroughs. Mr. Burroughs served for thirty years as chairman of the board of the successor company to Myrtle Beach Farms. He had been involved in the 1971 negotiations, and he gave me added background from the other side of the transaction. He was intimately familiar with it, and he explained that some of my previous information had not been entirely accurate.

The Burroughs older generation wanted to sell Myrtle Beach Farms for liquidity and because they felt there was no younger successor management to run the company. Younger family members were greatly dissatisfied with the price that was being agreed to – $25 million. Our own RJR appraisers valued the assets at over $65 million, while some family believed that they were worth much. They did not want to sell for a third of fair market value – a great deal for R. J. Reynolds and a very poor deal for the Burroughs family.

The Chapin family from Chicago who partnered with the Burroughs family in a deal made in the early 1900s controlled 50% of Myrtle Beach Farms. Burroughs & Collins, the original company founded in Conway South Carolina owned the other 50%.

The older Burroughs family members were sure that they had the support of enough voting stock to complete the sale, but a clause in the Burroughs & Collins bylaws required that two-thirds of the shares had to approve the sale of Myrtle Beach Farms, and there was not sufficient shareholder support. So, my belief that RJR was responsible for the deal falling through was not correct. The Burroughs family themselves never reached an agreement internally. Soon after, the company still under family control, had a major change of management. Not uncommon in a family business, there had been some dissatisfaction among themselves and they opted to bring in outside management. This proved to be more than satisfactory over the years, and the property has become far more successful than I had imagined.

My estimate had been that the Myrtle Beach properties might be worth as much as $3 billion today. That undeveloped strip of choice beachfront so praised by Bill Lybrook now has a luxurious Marriott Hotel and several multi-million-dollar homes and condos.

Myrtle Beach Farms has become a Real Estate Investment Trust, Burroughs & Chapin. The business has expanded with holdings along the coast in Wilmington, Charleston, and Savannah. The former chairman would not reveal the value of the closely held company, but he suggested that my $3 billion estimate was low.

Egerton Burroughs spoke highly of Buddy Kemp and the people at Bank of America. B of A is still Burroughs & Chapin’s lead banker, a relationship that goes back to well before the turn of the twentieth century, perhaps as much as one hundred forty years to a predecessor bank that was located in Conway.

In its early days just after the Civil War, Burroughs & Collins was active in many businesses –even growing tobacco. Mr. Burroughs explained that they exited the tobacco business because they were afraid that lawsuits would be brought against not only the makers of cigarettes but also the tobacco retailers and tobacco farmers. Not wishing to be exposed to such potential legal liability, they exited tobacco farming.

Following is a chronology of Myrtle Beach, a story that spans 180 years.

History of Myrtle Beach Farms

Before the Civil War, Franklin Burroughs began a turpentine and mercantile business in Conway, South Carolina. After service in the Civil War, Burroughs returned to Conway and formed a partnership with Benjamin Grier Collins, a native of nearby Georgetown County. The two men expanded the company’s commercial interests into tobacco farming, timber, farm credit, consumer goods, riverboats, and, eventually, the first railway through the swamps of Horry County to the beaches of what is the Grand Strand.

1897 – Shortly before his death, Franklin Burroughs envisioned the Grand Strand, then known as New Town, as a popular seaside destination with unlimited potential for future growth. Burroughs died before his efforts to link the beach, via railroad came to fruition.

1900 The sons of Franklin Burroughs complete the first railroad between Conway and New Town on the beach. In a contest to name the new community by the sea, Burroughs’ widow, Miss Addie, suggested “Myrtle Beach” for its abundance of the native wax myrtle shrubs.

1901 – The Burroughs family built the Seaside Inn, the first oceanfront hotel in Myrtle Beach. A bathhouse, wooden pavilion, and beach houses followed.

1912 – Simeon B. Chapin a New York stockbroker and son of a prominent Chicago merchant, joined with the Burroughs brothers to form the Myrtle Beach Farms Company. Chapin’s financial resources and business experience along with the Burroughs’ vast real estate holdings provided for a period of sustained economic growth. The landmark Myrtle Beach Pavilion was expanded, a downtown shopping district took shape around The Chapin Company General Store and Myrtle Beach Farms residential real estate development served the needs of a growing community.

1948 – While several “Pavilion” structures had stood on this site since around 1908, the new Myrtle Beach Pavilion & Amusement Park opened on the oceanfront, featuring an expansive boardwalk, bathhouse and several acres of rides and other attractions. “Mr. Edward Burroughs, one of the senior Burroughs executives who helped design and build the last Pavilion, had strict rules about the property. It was a family-oriented playground, and he did not allow alcohol on the premises. When the Pavilion was built and opened in 1948, little did anyone know that the whole world would be coming.” (1)

1975 – The company opens Myrtle Square Mall, the largest and first completely enclosed shopping center in northeastern South Carolina.

1990 -Myrtle Beach Farms Company joined Conway-based Burroughs & Collins to form Burroughs & Chapin Company, Inc.

2001 -Burroughs & Chapin launched Grande Dunes, a 2,200-acre resort and residential community stretching from the Atlantic Ocean to the west of the Intracoastal Waterway.

2006 – The Myrtle Beach Pavilion closed. It has been a nostalgic landmark for untold numbers of vacationers. The Pavilion is also cited by some as the birthplace of South Carolina’s state dance: The Shag. “The Pavilion was the highlight of generations of teenagers. They would gather around the Myrtle Beach Pavilion and out on the patio with the jukebox and dance the night away.”

2014 – Burroughs and Chapin shareholders approved conversion into a real estate investment trust.

2018 – The Burroughs & Chapin REIT has been highly successful and has extended its real estate holdings to Wilmington, Charleston, and Savannah.

Wikipedia. “Burroughs & Chapin.” Last updated April 19,2020. Accessed July 6, 2020. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Burroughs_%26_Chapin

Ashley Talley. “It was our Disney World:’ Remembering the Myrtle Beach Pavilion.” WMBF News, June 15, 2017. https://www.wmbfnews.com/story/35668581/it-was-our-disney-world-remembering-the-myrtle-beach-pavilion/