Newlin on Sea-Land

Locke found that the problem could be “boiled down to one word, competition.” Sea-Land had lost its edge in the market faster than expected.

Newlin also soon found that Sea-Land had a trucking culture, not a shipping culture. He described the business this way:

“The division heads were all salesmen. They started out as trucking salesmen – not businessmen, salesmen. They knew nothing about costs. Sales were what pumped them up. Selling freight is hard; it is a commodity. Customers don’t care what the ship looks like. They don’t even care how fast it gets there. If they need “fast” they send it by air. For example, the West Coast food processors would ship product to the East Coast through the Panama Canal so that property taxes were not levied because the goods were on the water. They want regular, dependable service. So, Sea-Land made a weekly call at each port on a certain day. Old ships made these domestic runs to comply with the Jones Act, a 1920 federal law that goods moving between U.S. ports be transported on ships built, owned, and operated by U.S. citizens or permanent residents.”

Unfortunately for Locke, he continually delivered bad news on profits, and the recipients did not always take that news gracefully.

Winston-Salem began to challenge Sea-Land accounting. After about two years. Locke brought Dave Herring from RJR to handle the Capital Expenditure (Capex) accounting. (I worked with Dave briefly in 1977 on the D-9 ship project. He had a long career in the shipping industry and is still a maritime consultant.)

But cost accounting was not going well. Vessel accounting used a method called “Completed Voyage.” At the end of a trip, accounting would create a Vessel Voyage Profit & Loss Statement (P&L). This entailed booking the revenue when the ship sailed and accruing estimated costs. True costs did not come in until later, and they seemed to always exceed the original accruals. Some bills didn’t arrive for a month, while revenue was realized immediately. This was referred to as “beyond days” accounting. Even the original costs at port were estimates, often big surprises, and always unfavorable. Stevedore, terminal, warehousing, LTL (less than truckload) costs were hard to estimate. Very unlike simple tobacco accounting, this too drove a wedge between the two groups.

Locke had to prepare profit forecasts. Mike McEvoy (Sea-Land CEO), was a capable and funny man whose specialty was labor relations. Each time he met Lock in the building, he would say, “Here comes that Newlin guy, pissing on my rainbow.”

Sea-Land had grown from an idea into a rapidly expanding company that introduced new technology to the world. It was a classic example of a young company built by a creative entrepreneur where people suddenly found themselves answering to bureaucratic, rules-oriented management.

The way many Sea-Landers saw it – RJR criticized Sea-Land’s operations from the start and tightened control, blasting the Sea-Land managers for sloppy accounting. Such criticism did not sit well. The Sea-Land people knew that their entrepreneurial culture had kept the company flexible. They made decisions quickly and sometimes sealed commitments with a handshake.

Even as Malcolm McLean was removing himself from active management, he still gave attention to three areas:

- Union negotiations. Sea-Land had six unions on ships as well as Teamsters and International Longshoremen (ILS). He wanted to be sure management made no promises it couldn’t keep.

- Shipbuilding. First the SL-7s, then U.S. Lines. He wanted the vessels to be dominant.

- Military contracts. Military business required a U.S. flagship with a U.S. crew. From 1967-73 Sea-Land delivered 1,200 containers per month to Indochina, $450 million in revenue. McLean believed military business was like a subsidy. Most freight was inbound to the U.S. (and still is, except commodities.) Military business filled the vessels outbound. Sea-Land never lost a military contract, and they were very lucrative. McLean set up a Viet Nam company, Equipment Inc. It hauled all inland freight from two ports to inland bases. Equipment Inc. made lots of money under its contracts. In those days the government had a renegotiation board. The government could revisit a contract years after it was closed and demand some money back because of excess profits. McLean was well up on international law in this area.

Sea-Land had other problems. It was a member of various “conferences,” government-sanctioned cartels that set rates. Sea-Land created an off-books account in Hong Kong at Hang Seng Bank. It made kickbacks to customers, and the IRS found out. The IRS had Sea-Land under audit for three years. When he first went to Sea-Land, Newlin would ask what was in certain accounts, and people would laugh. “When you ask an accounting question and people giggle, your nose tells you there’s a problem.” He had to account for costs so “on books” fed the “off-books” accounts.

Any time RJR people came to Sea-Land headquarters for a meeting, they invited Newlin. He was accused of being a spy, and by 1972, things were “getting hot” because he was so often the bearer of bad news in rough times. Sea-Land Accounting was moved to Winston-Salem, and Newlin continued to head the function there until 1975.

When Locke Newlin moved to Sea-Land, its management had already considered building eight S-L7s . These ships were plagued with problems – financial and operational.

Construction proceeded on five ships in Germany and three in the Netherlands. The annual report listed their interim financing (at December 31, 1970 exchange rates) with banks in Germany and the Netherlands – to be replaced with long-term foreign financing as the vessels were completed.

Bank financing repayment schedule

(Dollars in Thousands)

1972 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .$ 1,590

1973 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12,322

1974 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19,322

1975 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19,322

1976 and thereafter . . . . . . .. . 161,326

$ 213,882

This debt would reveal later just how little RJR knew about international finance. Reynolds was “so internationally uninformed” that they borrowed the money in German and Dutch currency where they got a good interest rate. Immediately, the dollar weakened. RJR paid much more because it had not hedged the currency, spending nearly twice as many U.S. dollars as they had expected.

On Sunday night August 15, 1971, President Nixon moved the U.S. off the Gold standard so currencies would begin to trade at a floating exchange rate. RJR people knew this was a problem, given its foreign currency commitment.

I was at Chase Manhattan Bank in New York the next morning. The stock market soared on the news, even though pundits had always declared that leaving the gold standard would be disastrous for security markets. I called Winston-Salem and said I supposed RJR treasury people would soon be heading to Germany and the Netherlands about our debts there. I was told, “They didn’t wait until today, the Treasurer left for Europe last night, right after Nixon’s speech.’ He knew we were in trouble.

The contracts for the entire price of the ships was in foreign currency, so RJR paid on both the purchase price and the debt. The annual reports carefully skirted this issue and said little about it. [Judging from the annual report, the debt cost about $125 million in currency exchange losses and the SL-7s were booked at $600 million, $200 million over the original stated price] In all, the $400 million ships really cost $775 million.

****

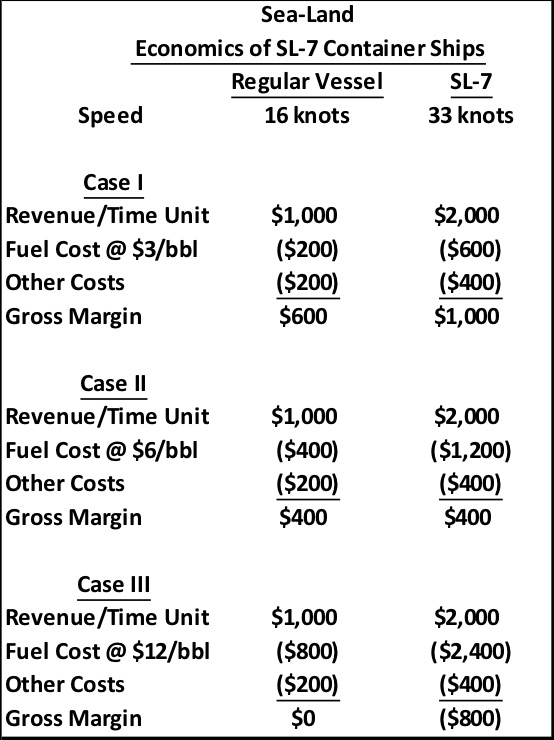

Bob Thompson, head of Business Planning implemented a system using a PEP form (Property Expenditure Proposal). Management submitted a PEP to study the economics of the old ships compared to the new SL-7s. Locke examined the bunker fuel comparison. Oil was $3 per barrel. The SL-7s guzzled fuel. If bunker doubled to $6 per barrel, the profits still looked “okay.” Newlin was ridiculed for suggesting an increase to even $6. Oil continued to march up to $12 in October 1973 and finally peaked at $39 in November 1980.

If a ship’s speed doubles, then as an operating asset, theoretically, it is twice as efficient. However, fuel consumption for a ship increases dramatically with speed. For example, a ship doubling its speed from 16 to 33 knots would require not twice as much fuel, but perhaps three times as much, an exponential increase. So, the major cost of the haul goes up 50% and the advantage is diminished. At some high fuel price, the entire economic advantage disappears.

If a ship’s speed doubles, then as an operating asset, theoretically, it is twice as efficient. However, fuel consumption for a ship increases dramatically with speed. For example, a ship doubling its speed from 16 to 33 knots would require not twice as much fuel, but perhaps three times as much, an exponential increase. So, the major cost of the haul goes up 50% and the advantage is diminished. At some high fuel price, the entire economic advantage disappears.

The SL-7 also had a design problem. No one had ever tried to get 33 knots from a vessel like this one. At 33 knots, the ship cavitated; the props rattled.

Sea-Land sold the vessels to the U.S. Navy in 1981-82 for $268 million. The Navy wanted fast ships to carry weaponry to battle areas. They were converted to roll on/roll off (RoRo) to carry tanks and other vehicles. Due to their high operating cost, all eight ships are in Reduced Operating Status but can be activated and ready to sail in ninety-six hours. In a war, fuel cost would not be important.

The U.S. was in an inflationary spiral and replacement accounting was in vogue. Historical accounting didn’t mean much with prices rising ten percent or more each year. At a security analyst meeting, Charlie Hiltzheimer, COO of Sea-Land was pointing out how much it would cost to replace the SL-7s. To make the point about the utility of an asset related to its replacement cost, Frank Power whispered to Locke Newlin, “What if you wanted to build a new pyramid, what is the replacement cost.” Hiltzheimer’s comment was surely in defense of the SL-7s economic value. Frank Power was prophetic – the SL-7s finally proved to be about as profitable to Sea-Land as a pyramid.

But the biggest problem was the performance of the SL-7s. In 1973, these vessels fully deployed, and the timing could not have been worse. Late that year, the OPEC oil embargo, a protest against U.S. involvement in the Arab-Israeli War, drove oil prices up fivefold in just a few weeks. This played havoc with the bunker fuel costs, especially for the fuel-guzzling SL-7s that had been designed for high speed and low fuel cost.

The SL-7s had a second serious setback in 1975. The Suez Canal closed since 1967, unexpectedly reopened. This canal handled about 7.5% of world trade. Suez reduced the shipping distance from Asia to London by 4,600 miles. This negated much of the advantage of the high-speed SL-7s which offered much faster delivery when ships had to sail around the southern tip of Africa.