RJR Preferred “B”

To say that the preferred stock treated Sea-Land people well is an understatement. Three examples show how they were rewarded for believing in Sea-Land and then in RJR.

Malcolm McLean got 3.65 million shares of the RJR Convertible Preferred Stock, representing 10.4% ownership of RJR. He had swapped a company that had heavy capital demands for a major stake in one that generated cash like the U.S. mint. His dividend income was $22,500 a day ($151,000, $2019).

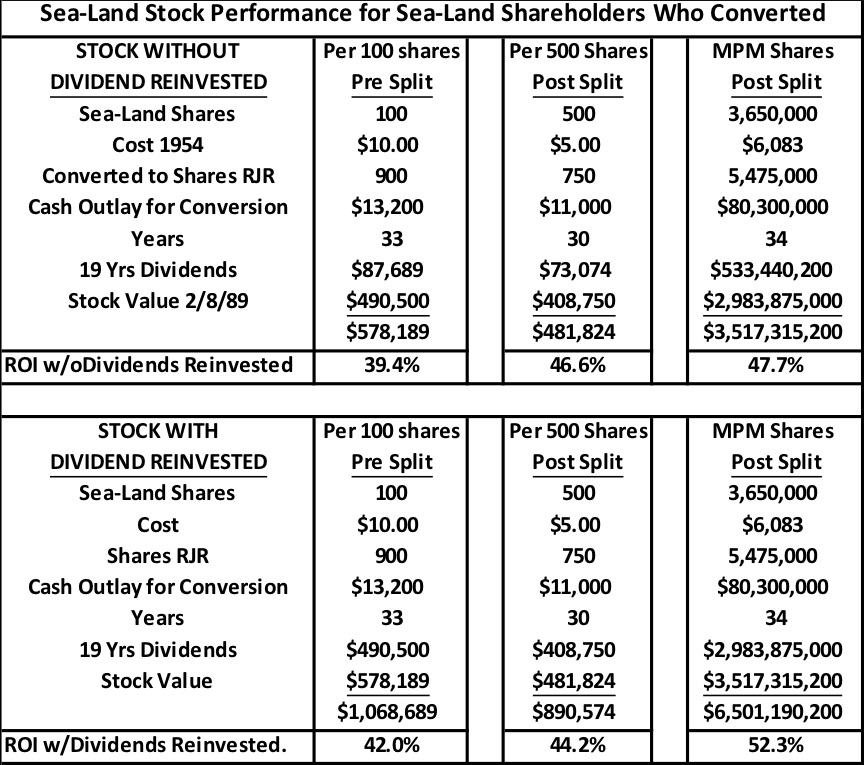

Malcolm’s return on his original Sea-Land stock was staggering. He told me that he capitalized his company initially at one cent per share and later split the stock six for one, making the cost in his $45.00 RJR stock just 1/6 cent per share. Malcolm’s total holdings would have been worth $3 billion with another $533 million paid in dividends. With dividends reinvested the total return would’ve been $6.5 billion.

****

One Sea-Land employee said, “One Christmas early in my career, Malcolm said to me, ‘We have no money for a bonus this year, and I know you have a family. Give me five dollars and you can have five hundred shares of my stock.’” He never forgot Malcolm‘s generosity, and to his everlasting credit he never sold a single share. He borrowed against his stock after the conversion, using broker margin, to support and educate his family. When the KKR buyout closed, that $5 investment returned him $73,000 in dividends and $409,000 for his shares. He deserves plaudits for having the courage to stay with the stock all those years. The risky decision paid off in a big way. He got the best $5 Christmas present that I ever heard, and he made the most of it.

****

And finally – one of the worst investment decisions ever made. In the very early days of Sea-Land, Malcolm lost a golf bet for $10 at the Old Town Club in Winston-Salem. He said to the winner, “Instead of $10, I’ll give you 100 shares of Sea-Land stock.” His golfing partner said, “I’d rather have the $10.” If that story is true, surely the man remembered it as one of the worst decisions in his life. But how could he have known at the time that the piece of paper he was being offered would, thirty-five years later, be worth $490,000 after already having paid him $88,000 in dividends?